Ecological monitoring is an important endeavour as we seek to understand the effects of environmental change on biodiversity. We need to benchmark the status of our fauna, and check-in on that fauna on a regular basis: in this way we can, for example, better understand how climate change might alter our earth systems. That’s kind of important.

A northern ground beetle, Elaphrus lapponicus. Photo by C. Ernst.

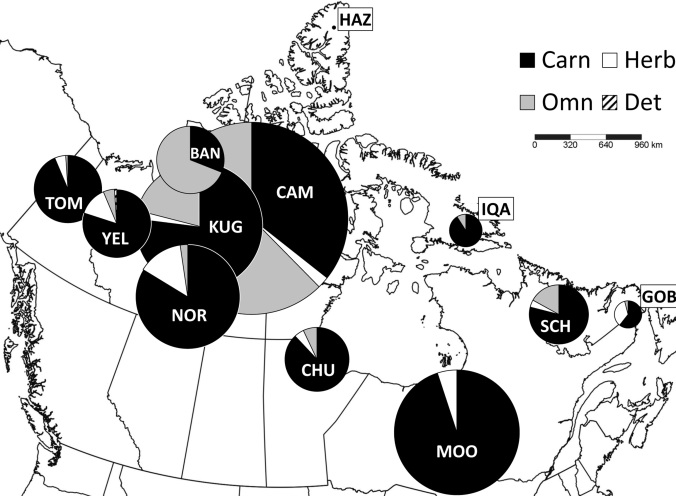

With that backdrop, my lab was involved with a Northern Biodiversity Program a few years ago (a couple of related papers can be found here and here), with a goal of understanding the ecological structure of Arthropods of northern Canada. The project was meant to benchmark where we are now, and one outcome of the work is that we are able to think about a solid framework for ecological monitoring into the future.

A few weeks ago our group published a paper* on how to best monitor ground-dwelling beetles and spiders in northern Canada. The project resulted in over 30,000 beetles and spiders being collected, representing close to 800 species (that’s a LOT of diversity!). My former PhD student Crystal Ernst and MSc student Sarah Loboda looked at the relationship between the different traps we used for collecting these two taxa, to help provide guidelines for future ecological monitoring. For the project, we used both a traditional pitfall trap (essentially a white yogurt container stuck in the ground, with a roof/cover perched above it) and a yellow pan trap (a shallow yellow bowl, also sunk into the ground, but without a cover). Traps were placed in grids, in two different habitats (wet and “more wet”), across 12 sites spanning northern Canada, and in three major biomes (northern boreal, sub-Arctic, and Arctic).

Here’s a video showing pan traps being used in the tundra:

Both of the trap types we used are known to be great at collecting a range of taxa (including beetles and spiders), and since the project was meant to capture a wide array of critters, we used them both. Crystal, Sarah and I were curious whether, in retrospect, both traps were really necessary for beetles and spiders. Practically speaking, it was a lot of work to use multiple traps (and to process the samples afterwards), and we wanted to make recommendations for other researchers looking to monitor beetles and spiders in the north.

The story ends up being a bit complicated… In the high Arctic, if the goal is to best capture the diversity of beetles and spiders, sampling in multiple habitats is more important than using the two trap types. However, the results are different in the northern boreal sites: here, it’s important to have multiple trap types (i.e., the differences among traps were more noticeable) and the differences by habitat were less pronounced. Neither factor (trap type or habitat) was more important than the other when sampling in the subarctic. So, in hindsight, we can be very glad to have used both trap types! It was worth the effort, as characterizing the diversity of beetles and spiders depended on both sampling multiple habitats, and sampling with two trap types. There were enough differences to justify using two trap types, especially when sampling different habitats in different biomes. The interactions between trap types, habitats, and biomes was an unexpected yet important result.

Our results, however, are a little frustrating when thinking about recommendations for future monitoring. Using more than one trap type increases efforts, costs, and time, and these are always limited resources. We therefore recommend that future monitoring in the north, for beetles and spiders, could possibly be done with a trap that’s a mix between the two that we used: a yellow, roof-less pitfall trap. These traps would provide the best of both options: they are deeper than a pan trap (likely a good for collecting some Arthropods), but are yellow and without a cover (other features that are good for capturing many flying insects). These are actually very similar to a design that is already being used with a long-term ecological monitoring program in Greenland. We think they have it right**.

A yellow pitfall trap - the kind used in Greenland, and the one we recommend for future monitoring in Canada’s Arctic.

In sum, this work is really a “methodological” study, which when viewed narrowly may not be that sexy. However, we are optimistic that this work will help guide future ecological monitoring programs in the north. We are faced with increased pressures on our environment, and a pressing need to effectively track these effects on our biodiversity. This requires sound methods that are feasible and provide us with a true picture of faunal diversity and community structure.

It looks to me like we can capture northern beetles and spiders quite efficiently with, um, yellow plastic beer cups. Cheers to that!

Reference

Ernst, C, S. Loboda and CM Buddle. 2015. Capturing Northern Biodiversity: diversity of arctic, subarctic and northern boreal beetles and spiders are affected by trap type and habitat. Insect Conservation and Diversity DOI: 10.1111/icad.12143

——

* The paper isn’t open access. One of the goals of this blog post is to share the results of this work even if everyone can’t access the paper directly. If you want a copy of the paper, please let me know and I’ll be happy to send it to you. I’m afraid I can’t publish all of our work in open access journals because I don’t have enough $ to afford high quality OA journals.

** The big caveat here is that a proper quantitative study that compares pan and and pitfall traps to the “yellow roof-less pitfall” traps is required. We believe it will be the best design, but belief does need to be backed up with data. Unfortunately these kind of trap-comparison papers aren’t usually high on the priority list.