I field a lot of questions about spider bites, and I have argued that spider bites are exceedingly rare (for humans). But what about our pets? Do our furry friends get bitten by spiders? If they get bitten, how do they react? Let’s look at this, move beyond anecdotes, and see what science has to say on the topic!

Can spiders bite my dog or cat?

The short answer to this is: YES. Some spiders are physically capable of biting mammals, including dogs and cats.

This is my dog, Abby. Should she be scared of spiders?

The longer answer is that we really don’t know about this for the vast majority of spider-pet interactions, and even if spiders can bite mammals, I would argue that such events are relatively uncommon. Spiders certainly don’t hunt dogs or cats, and when bites do occur, they are likely quite accidental. Your puppy Ralph can be quite energetic and rambunctious, and stick his snout into a dark corner which may be home to an arachnid. I’ve certainly seen my cat “play” with insects and spiders, and ping-pong an arthropod across the kitchen floor. However, we certainly have to get a little lucky to see an actual spider-pet interaction, and dogs and cats can’t tell us whether they have been bitten by a spider. Proper verification of any bite requires evidence.

In some cases, the evidence isn’t in dispute, such as the paper by O’Hagan and colleagues who state quite clearly in their peer-reviewed paper:

“Two 9-week-old Chihuahua pus weighing 960 grams and 760 grams were seen to be attacked and bitten by a large black spider. The spider was killed” (O’Hagan et al. 2006).

Right: the puppies were seen to have been bitten by a spider, and presumably the pet-owners know what a spider looks like. Also, that paper was co-authored by a well-known Arachnologist, Dr. Raven – having an arachnologist involved in these studies is important, and gives credibility to the incident. This is a good example of a verifiable interaction between dogs and spiders.

There’s another detailed paper by Isbister et al., outlining spider bites (in the family Theraphosidae, a family of Tarantula spiders) in humans and dogs: their evidence isn’t in dispute either, and in two cases, the human was bitten just after the dog was bitten. That’s pretty clear!

Without clear evidence, however, it becomes tricky: there’s a case report of a Brittany spaniel being brought to a hospital, with “swelling on its muzzle, left of the midline” (Taylor & Greve 1985). This became a ‘suspected’ case of loxoscelism, and assumed by the authors to be caused by the brown recluse spider. However, diagnosis of loxoscelism is very difficult, and other more probably causal agents could be investigated. Stated another way: it may not be the spider. Don’t blame the spider without adequate evidence. As Rick Vetter states on his excellent website:

“There are many different causative agents of necrotic wounds, for example: mites, bedbugs, a secondary Staphylococcus or Streptococcus bacterial infection. Three different tick-inflicted maladies have been misdiagnosed as brown recluse bite…” (Rick Vetter, accessed Feb 9 2015)

It’s also very tricky to look at a ‘wound’ on a pet and determine whether or not a spider was involved. I would suggest if there are multiple wounds, or lacerations, multiple bumps and bruises, it is unlikely to have been caused by a spider, and other more likely causal agents should be investigated (e.g., punctures, skin reaction to something, or perhaps an insect sting, or fleas).

So, bottom line: although I think direct interactions between spiders and our pets are relatively rare, spiders are certainly capable of biting our dogs or cats.

Do cats and spiders mix?

What happens if my pet is bitten by a spider?

If there is clear evidence that a spider bit your pet, there are really only two outcomes: nothing will happen (or your pet may exhibit mild reactions that may not be immediately obvious), or there will be clear, definable symptoms, and these may lead to more serious consequences.

I think the first scenario is more common than the latter, largely because we just don’t have a good way of tracking the frequency of spider-pet interactions, and as is the case with humans, the vast majority of spiders probably aren’t venomous to our pets. Our pets certainly get ‘mildly’ sick all the time – I think of the times that my dog got an upset stomach, and I always assume she tracked down some ‘snacks’ when on an off-leash run (I think she is quite fond of rabbit droppings…).

Science does provide us some data about more serious reactions when our pets do get bitten by certain spiders. The paper by Isbister et al., from 2003, is quite detailed, and gives case studies of a number of verified bites by spiders on humans and canines in Australia. Here’s the alarming part:

“There were seven bites in dogs, and in two of these the owner was bitten after the dog. In all seven cases the dog died. In one case… the Alsatian died within 2 h of the bite. In two cases small or juvenile dogs died in less than an hour…” (Isbister et al.)

In this paper, the effects on humans were relatively minor, but this was not the case for our furry friends - reactions were severe and fast and resulted in death. The poor little Chihuahua pups mentioned earlier were equally unlucky, as reported by O’Hagan et al. Although both of these studies were from Australia, and involved only one family of spiders, it’s certainly scientifically interesting that canines were affected so strongly, and their reactions provide opportunities to further research the components of spider venom (e.g., see Hardy et al 2014).

There is also some evidence that cats may be affected by spider venom: research reported by Gwaltney-Brant et al, and Hardy et al, stated that toxicity studies result in fatalities of our feline friends:

“Cats are very sensitive to the effects of widow venom. In one study, 20 of 22 cats died after widow-spider bites, with an average survival time of 115 h. Paralysis occurs early in the course; severe pain is evidenced by howling and other vocalizations…” (Gwaltney-Brant et al.*)

That’s pretty grim. Interestingly, this case reports on envenomation by widow spiders in the genus Latrodectus (e.g., the genus that includes all the black widow spiders that occur in North America) - these spiders are relatively common in some habitats, and can certainly live in proximity to humans. Looking at Australia again, Hardy et al. state that cats are seemingly unaffected when bitten by female funnel-web spiders in Australia. So, effects of spider venom on cats and dogs differs depending on the type of spider, and even our pets aren’t likely to respond the same way to different kinds of spiders. Clearly, it is difficult to generalize about any of this!

In sum, I have presented some details about spiders and how they might interact with our beloved pets. It’s fair to say that our pets certainly may get bitten by spiders, but overall I would argue such interactions are relatively rare. However, dogs and cats are certainly not immune to spider venom, and there is evidence to suggest they might have strong negative reactions to spider bites.

Despite this, I don’t see this as reason to panic or start stomping on any arachnid that wanders across your living room floor. The evidence we have is still relatively limited, and we just don’t have much information about effects of venom on pets, for those spiders that commonly inhabit our homes. I also think the lack of evidence is important to mention: if our pets were getting bitten by spiders on a regular basis, there would be more papers on the topic, and certainly more cases where anecdotes made the transition to evidence.

I think it’s possible to love your pets AND be an arachnophile. That’s certainly how I live my life.

[A BIG thanks to Maggie Hardy, Daniel Llavaneras and Catherine Scott, for helping point me to literature on this topic]

References:

Hardy, M.C., J. Cochrane and R.E. Allavena (2014). Venomous and Poisonous Australian Animals of Veterinary Importance: A Rich Source of Novel Therapeutics. Biomed Res. Intl. doi: 10.1155/2014/671041

Isbister, G.K. J.E. Seymour, M.R. Gray, R.J. Raven (2003). Bites by spiders of the family Theraphosidae in humans and canines. Toxin doi:10.1016/S0041-0101(02)00395-1

Gwaltney-Brant, S.M., E.K. Dunayer and H.Y. Youssef. (2007) Terrestrial Zootoxins. Ch. 64 in Veterinary Toxicology (Edited by R. C. Gupta).

O’Hagan, B.J., R.J. Raven, and K.M. McCormick (2006) Death of two pups from spider evenomation. Aust. Vet. J. 84: 291

Taylor, S.P. and J.H. Greve. (1985) “Suspected Case of Loxoscelism (Spider-bite) in a Dog,” Iowa State University Veterinarian: Vol. 47: Iss. 2, Article 1.

—-

© C.M. Buddle (2016)

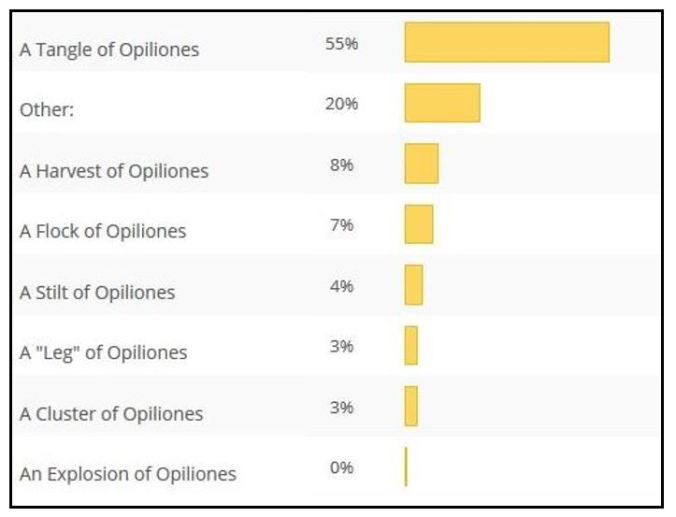

And some of the “other” suggestions:

And some of the “other” suggestions: