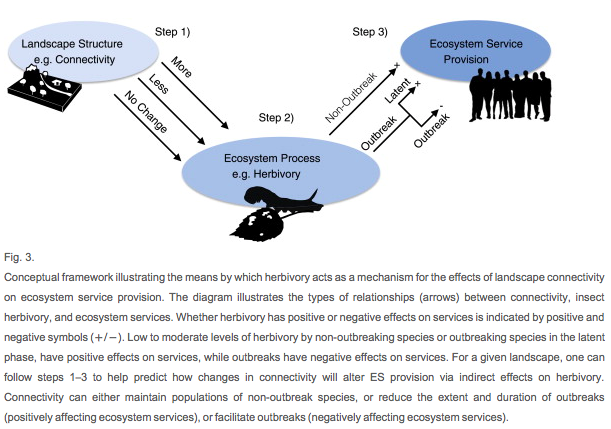

I’m excited to announce a recent paper to come out of the lab, by former PhD student Dorothy Maguire, and with Dr. Elena Bennett. In this work, we studied the amount of insect herbivory in forest patches in southern Quebec: the patches themselves varied by degree of fragmentation (ie, small versus large patches) and by connectivity (ie, isolated patches, or connected to other forest patches). We studied herbivory on sugar maple trees, both in the understory and canopy, and at the edges of the patches. Our research is framed in the context of “ecosystem services” given that leaf damage by insects is a key ecological process in deciduous forests, and can affect the broader services that forest patches provide, from supporting biodiversity through to aesthetic value. Dorothy’s research was part of a larger project about ecosystem services and management in the Montérégie region of Quebec.

Dorothy Maguire sampling insects in the tree canopy (Photo by Alex Tran)

The work was tremendously demanding, as Dorothy had to select sites, and within each site sample herbivory at multiple locations, including the forest canopy (done with the “single rope technique). Dorothy returned to sites many times over the entire summer to be able to assess trends over time. Herbivory itself was estimated as damage to leaves, so after the field season was completed, thousands of leaves were assessed for damage. The entire process was repeated over two years. Yup: doing a PhD requires a suite of skills in the field and lab, and there is no shortage of mind-numbing work… Dedication is key!

As with most research, we had high hopes that the results would be clear, convincing, and support our initial predictions - we certainly expected that forest fragmentation and isolation in our study landscape would have a strong effect on herbivory - after all, our study forests varied dramatically in size and isolation, and herbivory is a common and important ecological process, and insect herbivores are known (from the literature) to be affected by fragmentation.

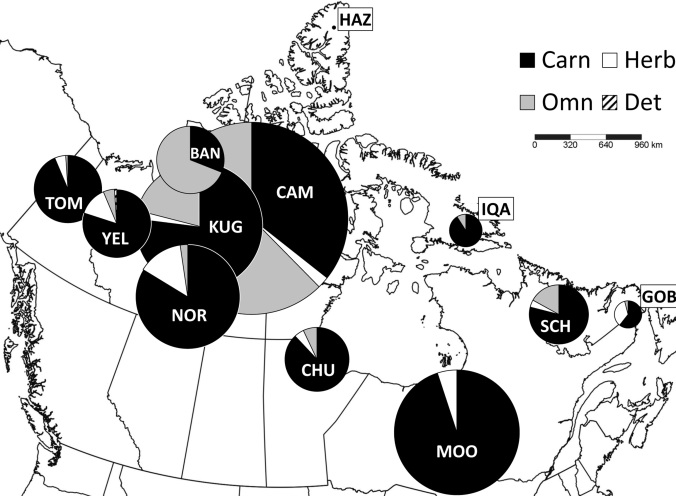

The landscape of southern Quebec. Lots of agriculture, some patches of forest.

However, as with so much of ecological research, the results were not straightforward! “It’s complicated” become part of the message: patterns in herbivory were not consistent across years, and there were interactions between some of the landscape features and location within each patch. For example, canopies showed lower levels of herbivory compared to the understory, but only in isolated patches, and only in one of the study years! We also found that edges had less herbivory in connected patches, but only in the first year of the study. Herbivory also increased as the season progressed, which certainly makes biological sense.

So yes, it’s complicated. At first glance, the results may appear somewhat underwhelming, and the lack of a strong signal could be viewed as disappointing. However, we see it differently: we see it as more evidence that “context matters” a great deal in ecology. It’s important not to generalize about insect herbivory based on sampling a single season, or in only one part of a forest fragment. The story of insect herbivory in forest fragments can only be told if researchers look up to the canopy and out to the edges; the story is incomplete when viewed over a narrow time window. In the broader context of forest management and ecosystem services, we certainly have evidence to support the notion that herbivory is affected by the configuration of the landscape. But, when thinking about spatial scale and ecosystem processes, careful attention to patterns these processes “within” forest patches is certainly required.

We hope this work will inspire others to think a little differently about insect herbivory in forest fragments. Dorothy’s hard work certainly paid off, and although the story is complicated, it’s also immensely informative and interesting, and sheds light on how big landscapes relate to small insects eating sugar maple leaves.

Reference:

Maguire et al. 2016: Within and among patch variability in patterns of insect herbivory across a fragmented forest landscape. PlosOne DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150843