A little while ago my nephew asked me what my favourite spider was. I quickly answered “Peckhamia picata“, in part because I had recently returned from a field trip in which that species was collected (a trip to one of my favourite places in Quebec), but also because the species has the most amazing habitus: is a myrmecomorph - a species that looks a heck of a lot like an ant. Here’s a photo to illustrate this:

A species of jumping spider in the genus Peckhamia (photo by Alex Wild, reproduced here with permission)

So, what does this species do? What are its behaviours? Where does it live?

I started digging around to see what literature exist on this species. There are certainly many publications that discuss its distribution - it is on many checklists (see here for a relatively complete list), and I was aware that it was originally described as Synemosyna picata (by Hentz, in 1846).

I did a search of Web of Science for publications with the species name, and came up with two hits. One was a systematics papers on a related genus of jumping spider, and the second was a paper by Durkee et al. in 2011*. They did some laboratory studies of the species, to assess whether or not its ant-like appearance helped it avoid being eaten by predators (spoiler: the answer is yes). A little more digging on-line took me to various sites, and in some cases, I came across this statement: “almost no information on them”

What? Really?

A Peckhamia picata, from Quebec (Photo by J. Brodeur, reproduced here with permission)

Peckhamia picata is a widespread species, with an incredible appearance, and it’s a jumping spider! Salticids are the darling of the arthropod world -> the panda bears of the invertebrates: big eyes, furry, fascinating courtship behaviours, and truckloads of ‘personality’. Surely we know SOMETHING about what I declared as my favourite species.

Thankfully, in a filing cabinet in my laboratory, I have a series of older publications on the Salticidae, including “A Revision of the Attidae of North America” by Peckham & Peckham (1909) [available here as a PDF download - note: big file!]. The George and Elizabeth Peckham did an incredible amount of work on the Salticidae (called Attidae, previously). The Peckhams are themselves a fascinating story - some details are on their Wikipedia page and I’ll summarize briefly: they were teachers (in Wisconsin), natural historians, behavioural ecologists and taxonomists, notably with jumping spiders. The bulk of their work was done in the late 1800s, and they often cited and discussed Darwinian concepts. They were awesome and I would have liked to meet them.

So, back to Peckamia picata: Their 1909 tome states the following about the species “We have described in detail its mating and general habits in Vol. II, Part 1 of the Occ. Pap. Nat. Hist. Soc. Wis. pp. 4-7)”.

So, apparently 1909 does not take us far enough back in history to learn about Peckhamia picata. Their paper from 1892 had all the details, and thankfully was fully accessible on the biodiversity heritage library.

Here is some of the lovely writings about Peckhamia picata, from the Peckhams, in 1892 (transcribed from their papers):

About appearance:

“While picata is ant-like in form and colour, by far the most deceptive thing about it is the way it which it moves. It does not jump like the other Attidae [Salticidae], nor does it walk in a straight line, but zig-zags continually from side to side, exactly like an ant which is out in search of booty. This is another illustration of which Wallace has shown in relation to butterflies ...”

(note: The Peckhams give a node to that Wallace guy….)

About feeding behaviour:

“Spiders commonly remain nearly motionless while they are eating; picata, on the other hand, acts liks an ant which is engaged in pulling some treasure-trove into pieces convenient for carrying I have noticed a female picata which, after getting possession of a gnat, kept beating it with her front legs as she ate, pulling it about in different directions, and all the time twitching her ant-like abdomen”

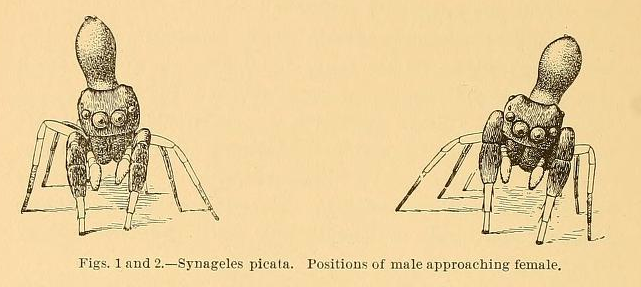

Regarding courtship:

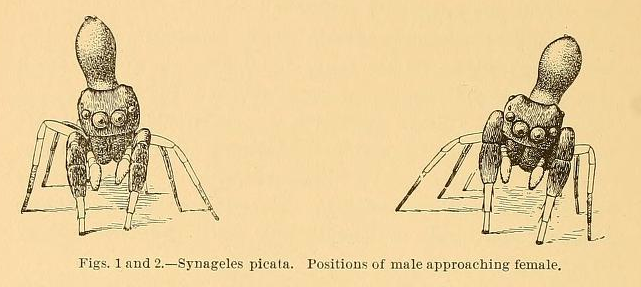

From the Peckham’s 1892 publication.

“His abdomen is lifted vertically so that it is at right angle to the plane of the cephalothorax. in this position he sways from side to side. After a moment he drops the abdomen, runs a few steps nearer the female, then then tips his body and begins to sway again. Now he runs in one direction, now in another, pausing every few moments to rock from side to side and to bend his brilliant legs so that she may look full at them.”

In sum, this journey of discovery has made me fall in love with Peckhamia picata even more. It’s also reminded me that OLD literature is essential to our current understanding of the species we identify. There is a wealth of information in these “natural history” papers - although the writing is in a different style, it is scientific, it is the foundation of current biodiversity science. We cannot ignore these older books and “Occasional papers”. We can’t rely on quick internet searches and we certainly can’t rely on literature indexed on Web of Science.

We must dig deep and far into the past. There are ‘treasure-troves’ aplenty.

—————-

*The oldest paper cited in Durkee et al. is from 1960. They did not cite the Peckhams.

Another Peckhamia species, courtesy of Matt Bertone (reproduced here, with permission)

References:

Durkee, C. A. et al. 2011. Ant Mimicry Lessens Predation on a North American Jumping Spider by Larger Salticid Spiders. Environmental Entomology 40(5): 1223-1231

Peckham, G.W., and E.G. Peckham. 1892. Ant like spiders of the family Attidae Occ. Pap. Nat. Hist. Soc. Wis. II, 1 .

Peckham, G.W., and E.G. Peckham. 1909. Revision of the Attidae of North America. Trans. Wis. Academy of Sci., Arts & Letters. Vol. XVI, 1(5), 355-646.