You may have heard about the latest insect pest to invade Quebec - it’s a small beetle, known as the Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis), that feeds on ash trees. The species has been detected in about 15 trees on the Island of Montreal, and it has made headlines in the local French and English press. In this post I wanted to provide some perspectives and context to this invasion, and ask whether this is a real threat, or mass hysteria.

The short answer: yes, the Emerald Ash Borer is a real threat to Ash trees, and it is VERY important for people to watch for this species.

Emerald Ash Borer, Photo from Forestry Images, Copyright: Debbie Miller, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org

The long answer: There is a lot of information on the Internet about this species, and I will not repeat it all here. Instead, I will try to stick to the main facts, and highlight some of the recent research that has been published about the species. I do recommend people spend time on the Canadian Food Inspection Agency’s (CFIA) website devoted to the species.

History of Introduction:

The Emerald Ash Borer is native to parts of Asia, and for that reason, it is considered as an Introduced species (or alien, or exotic) in North America. Many people use the word ‘invasive’ to describe the species -but this term should be paired with the word Introduced, as this species is invasive in the sense of spreading fairly quickly to new regions and introduced in the sense of not being indigenous to North America.

The Emerald Ash Borer probably arrived in North America in the 1990s (or even 1980s) but was not officially detected until the early 2000s, and that detection was in Michigan, and then almost simultaneously in Windsor, Ontario. It is believed that the species was introduced by accident through wood packing material - this is a very common route of introduction for a host of species, notably wood-boring beetles. Since the first detection, the species has been found in many regions of Ontario, Gatineau (Quebec), and it has been in Montreal for over a year (the first detection in Quebec was in Carignan, south of Montreal). It is likely that the introduction to Montreal was a separate (but related) introduction from elsewhere in Ontario or the USA - e.g., via movement of wood debris, firewood. It is unlikely that the Emerald Ash Borer came to Montreal through its own dispersal - if so, it certainly would have been detected in may regions between Montreal and SW Ontario.

Appearance, Habits, & Hosts:

The adult form of the beetle is quite attractive - the adults are rather small (about 8-14 mm in length - this is about the length of my own pinky finger-nail), metallic green, and its head is somewhat flattened and shield-like. It is fairly distinctive and I don’t think it is easily confused with any native species. It is in the family Buprestidae, which have the common name of “metallic wood boring beetles” - many Buprestids share a similar body shape (or habitus) to the Emerald Ash Borer. The larvae of the species is ‘grub-like’ in some ways (see below), and the larvae are the most active feeding stage -it’s at this stage that they feed underneath the bark of Ash trees, and can slowly kill the tree through their feeding activities (they essentially girdle the tree). It may take several years for tree mortality to occur.

The different life stages of the Emerald Ash Borer. Photo from Forestry Images, copyright, Debbie Miller, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org

The adults lay eggs on the host tree, and the larvae burrow into the bark, make “feeding galleries” (serpentine shaped), moult, grow, and eventually pupate and exit the tree through a ‘d-shaped’ exit hole - after pupation, the adults will eat leaves, fly around, mate, and the process starts again. Adults usually appear from mid-May until the early summer. Although not ‘vigorous’ flyers, the Emerald Ash borer can disperse many kilometres.

Galleries made by the larvae of the Emerald Ash Borer, photo from Forestry Images, (c) Michigan Department of Agriculture, Bugwood.org

The hosts of the Emerald Ash borer, as recorded in North America so far, are trees within the genus Fraxinus - i.e., ash trees. These are extremely common trees as both an ‘urban’ tree on streets and in parks within the city, but also occur naturally in local forests (e.g., the Morgan Arboretum). There is sometimes confusion about the “Mountain Ash” trees - this is not a ‘true’ ash, so it is not a host for the Emerald Ash borer.

Many species of wood-feeding beetles generally prefer to feed on, and complete their life cycles, on recently dead, weakened, and/or decaying trees. However, the Emerald Ash borer is different: it will feed upon and lay its eggs in healthy trees as well as weakened/damaged trees, and this is certainly one of the reasons why the species is of significant concern.

(Local) Management of the Emerald Ash Borer:

The city of Montreal (together with the CFIA) is taking the threat for the Emerald Ash Borer very seriously, including monitoring, targeted use of a bio-pesticide, and in providing information to the public, especially about movement and disposal of branches / firewood / yard scraps, etc. In some areas, a Ash-tree removal program has been used to stop the spread, with mixed results.

Education is extremely important with this pest: early detection is important to stop the spread, but so is limiting movement of any wood. Ash trees are not as recognizable as other species, and for that reason, when you have wood debris around, the city is asking you to call 311 for proper wood disposal. For further details, you can call you local municipally or click here for details. Again, the ability to detect the species will provide the best chances for limiting further spread and further damage. You ALL are invited to become an entomologist! Study the photographs of the Emerald Ash Borer and develop a search image - if you see the species in your yard, call 311, or your local municipal office and have the experts determine the best course of action.

Recent Research on the Emerald Ash Borer:

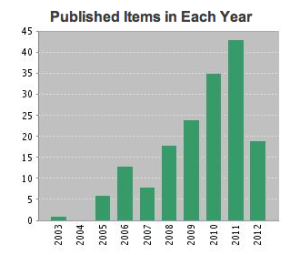

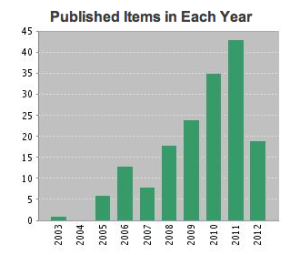

This has been a rather dramatic increase in the number of papers that have been published on Agrilus planipennis. Using that species name as a search term, you can see the increase in scientific interest based on the following graph pulled from Web of Science:

Number of publications, by year, on the Emerald Ash Borer, from Web of Science

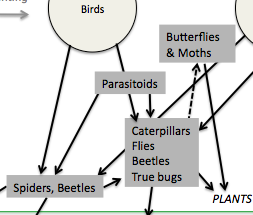

I am pleased to report that a biological control program has been started in the USA - parasitic wasps that use the Emerald Ash Borer as a host have been released, and are showing some potential at helping to control the pest - some good details are available here. Duan et al, have just published a paper reporting the incidence of parasitism for many hymenopteran parasitoids, and have also shown that woodpeckers account for a lot of mortality of the Emerald Ash Borer larvae, and ‘undetermined factors’ (includes diseases, potential host plant resistance) can also cause significant mortality (by the way, increased woodpecker activity on Ash trees could be a sign of an infestation).

Sobek-Swant et al. published a paper in January 2012 - they were curious about whether the species might be limited by cold winter temperatures - this is an important mechanism to test, especially at our (relatively) northern latitudes. However, under laboratory conditions, the authors found that the Emerald Ash Borer will unlikely be limited by ‘climatic’ factors, and instead, the presence of its host trees will be the most important factor. In other words: the species may eventually be found throughout the range of its host.

About a year ago, Ryall et al. published a very important paper on the Emerald Ash Borer. In this work, the researchers point out that the species is difficult to detect at low population levels, mainly because it make take several years before really noticeable mortality of Ash trees occurs. In other words, the larvae are ‘cryptic’ and may be doing damage before we can fully detect either the species or the damage to the tree. Detection methods can be destructive (e.g., stripping bark) so the authors propose using a relatively non-destructive branch-clipping technique to do monitoring for the species. This is something recommended to cities so that they can do broader areas of monitoring without destructive sampling. This can help significantly in pinpointing where the species is, and can help inform the best management strategy.

In 2011, Mercader et al. also published a paper of practical importance. In this work, the researchers simulated three management options for the Emerald Ash Borer to see which was most effective. Their three scenarios were: (i) removing the host tree (ii) girdling (killing) ash trees to attract ovipositing female beetles and destroying the trees before the larvae develop (this is a type of ‘trap tree’, i.e., you attract the species to a location and then trap and kill them) and (iii) applying a systemic insecticide. Their results suggest that the best way to stop or reduce the spread of Emerald Ash Borer is through the use of a systematic insecticide.

Outlook:

I am pessimistic that we will see success in eradicating the species from Montreal and surrounding areas, but slowing the spread is important and could allow for researchers to develop and fine tune other management options. Again, please educate yourself and learn what the Emerald Ash Borer looks like, and please do not move around wood and branches from your property to another location.

Emerald Ash Borer, on pin. Image from Forestry Images, (c) Pest and Diseases Image Library, Bugwood.org

References:

Duan, J., Bauer, L., Abell, K., & Driesche, R. (2011). Population responses of hymenopteran parasitoids to the emerald ash borer (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) in recently invaded areas in north central United States BioControl, 57 (2), 199-209 DOI: 10.1007/s10526-011-9408-0

Sobek-Swant, S., Crosthwaite, J., Lyons, D., & Sinclair, B. (2011). Could phenotypic plasticity limit an invasive species? Incomplete reversibility of mid-winter deacclimation in emerald ash borer Biological Invasions, 14 (1), 115-125 DOI: 10.1007/s10530-011-9988-8

Ryall, K., Fidgen, J., & Turgeon, J. (2011). Detectability of the Emerald Ash Borer (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) in Asymptomatic Urban Trees by using Branch Samples Environmental Entomology, 40 (3), 679-688 DOI: 10.1603/EN10310

Mercader, R., Siegert, N., Liebhold, A., & McCullough, D. (2011). Simulating the effectiveness of three potential management options to slow the spread of emerald ash borer populations in localized outlier sites

Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 41 (2), 254-264 DOI: 10.1139/X10-201

(thanks to Chris MacQuarrie for helping me with this post)