Yesterday I went back to the classroom and shadowed undergraduate students for the day. I did this because I just don’t really know what happens in classrooms. As an Associate Dean, I feel a responsibility to be aware of what students face throughout their day. I think this will help me gain perspective in my administrative role, and allow me insights into other instructional styles and approaches to teaching and learning in different contexts. After all, I really only know my way of teaching: I’ve not been an undergraduate student for a very long time.

Due to a bit of poor planning on my part, and since we are nearing the ‘end of term madness’, I wasn’t able to get a schedule for the whole day, and instead attended only three classes, with two different students. These students were my chaperones, and took me under their wing as they went to lecture or lab. By pure chance, I ended up seeing three different kinds of classes during my day, and have reflections about each of these experiences. In the first of this three-part blog series, I will share my experience taking part in an independent research project course.

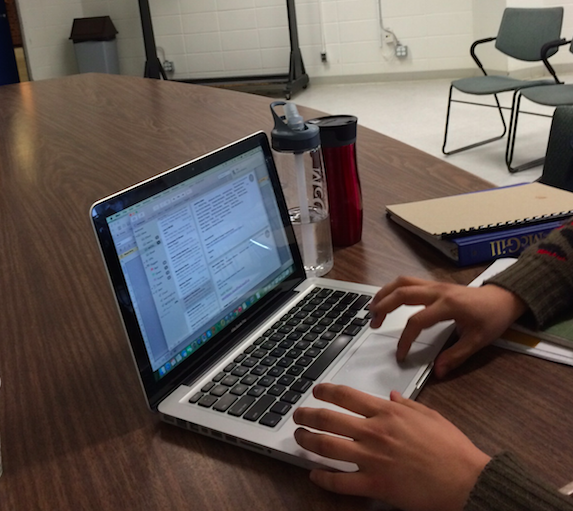

This was a very small class in which a few students were working on an independent project: their supervising Professor had recently given the group feedback on their written work, but was not present for this meeting. Instead, it was just the students and me (as a passive observer). Their project was centered on re-thinking environmental education with a goal of developing a framework or plan for teaching 9-12 year old kids about sustainability. The students were taking a very interesting approach in which their framework was focused on facilitating discussion around the values associated with teaching about sustainability: values such as respect, self-worth, respect and compassion. During our time together, the students edited a Google-doc together, and had deep and meaningful conversations about pedagogical principles. This was a wide-ranging discussion that was insightful, thoughtful and fascinating. To be honest, these students knew more about educational principles than most of my colleagues! They were in a science-based program, yet were reading literature from education journals, and were applying high-level thinking to a practical problem about how to create a learning opportunity based not on silos of knowledge, but on ways to approach sustainability from truly interdisciplinary perspectives.

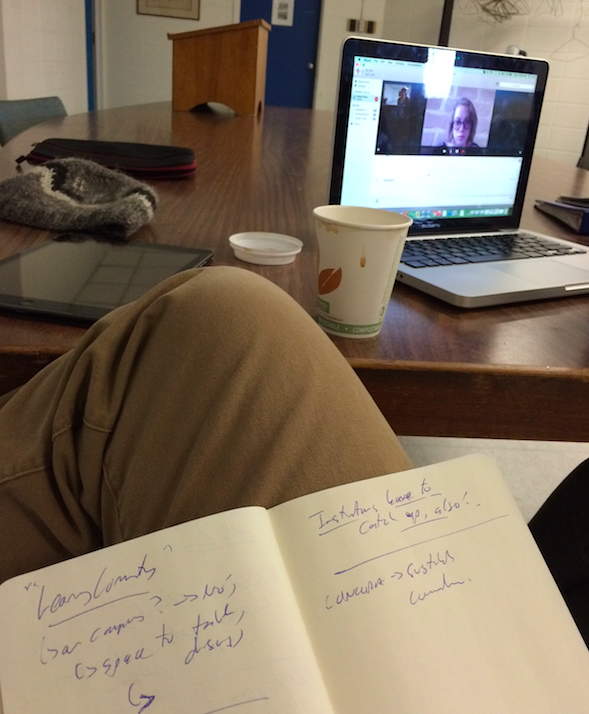

The discussion also moved into a conversation about teaching spaces: for this class, we were actually situated in a conference room, with a couple of chairs, a computer and one of the students was attending virtually, over SKYPE. This learning space was important to them, and at one point one of the students said “You get the most learning outside of the classroom”. Their ideal University is not one of lecture halls, but one of open spaces, whiteboards and WIFI: spaces for debate and discussion about big projects and problems that rely on multiple disciplines. The students expressed frustration that very few of their classes approach problems from interdisciplinary perspectives (or if they do, it barely moves beyond lip service) yet this is what they want from their education. They want a learning community that draws upon all the silos of knowledge at the same time, and they want spaces to facilitate this kind of learning.

These students amazed me with their insights, thoughtful commentary, and clear ideas about education, learning spaces, and expectations from a University experience.

My “Student for a day” project was off to a great start. Next up, a traditional lecture hall…