So you want to be an Arachnologist?

You just need to immerse yourself in the world of eight-legs: read, watch, connect, share & study.

I recently did an interview with a high school student from Indiana, who wanted to be an Arachnologist. This is not a common occurrence, in terms of a high school student expressing interest in this field of study, and because there are actually relatively few Arachnologists out there to act as role models!

I Tweeted about the interview, and a few people were quite intrigued by this, and asked me how they could train to be an arachnologist: a question worthy of a blog post! So, here are some thoughts and ideas, separating into three categories: elementary school, high school and finally, students entering college or University.

The younger years:

Kids like bugs. Children are naturally fascinated by arachnids: often not exhibiting as much fear as adults. They are curious, keen observers, and sponges for neat factoids about spiders and their relatives. At this age, responsibility for fostering arachnophiles really falls upon parents and teachers. Within the classroom, teachers should be encouraged to take kids outside, think about doing units/projects about natural history, and see about getting special activities into the classroom that focus on ‘biodiversity’. To me, it matters less that these activities are about spiders (or insects), but that they are celebrations of the natural world. It’s about keeping kids keen on the natural world continually engaged and interested in the natural world.

Parents can do a lot outside of the home - connecting with local naturalist clubs could help connect youngsters with some mentors and experts. Getting kids out to “Bug shows” is also a great idea - these are sometimes done through local museums, colleges or community centres. I always like to scroll through photos from these kinds of events: you can really see the enthusiasm on kids’ faces! Birthday parties could also be an opportunity to bring in biologists instead of clowns or princesses. A few quick web searches will reveal a suite of amazing workshops out there.

Bug shows: keeping kids exciting about arthropods. Photo by Sean McCann.

The teenage years:

I currently have two teenagers in my house, and this is a very interesting age: an age where habits get set, interests develop, and passions for hobbies either solidify or disappear. In the classroom setting this is where some students can really get turned on to science and biology, and for those keen on natural history, most students find the curriculum doesn’t satisfy as they are looking for a lot more. The high school student who interviewed me is a good example: she wanted to take courses more related to insects and spiders but such courses just don’t exist at high school - if lucky, they may just show up as part of the biology unit.

For those teenagers wanting to become arachnologists, some work is required. It may be possible to connect with local naturalists, or perhaps the nearest museum or college/University. These places may help facilitate the interests, and may even allow opportunities to have volunteers work with an insect of arachnid collection. Getting into an actual lab or research museum could be a positive life-changing experience for a teenager, but certainly isn’t an opportunity available to everyone.

I think during the teenage years the Internet and social media are invaluable tools. Heaps of information is available thought organizations such as the American Arachnological Society, or the International Society of Arachnology. Facebook groups or Twitter can also be a great way to connect with other Arachnologists: I personally use Twitter all the time to discuss spiders with colleagues from around the world, and these networks can also help spread the news about exciting discoveries in Arachnology.

Unfortunately it is rather difficult to recommend specific “spider courses” for teenagers wanting to become arachnologists. Instead, becoming an arachnologist at this age is really about learning what you can, wherever you can, and trying to connect with other arachnologists. For those wanting more academic pursuits, the best advice I can give to aspiring arachnologists is to become a good naturalist: observe, record, and be fascinated about the natural world. Good things will always come from this! In school, take the sciences and maths, especially biology, and when it’s time to head to College or University, think about selecting one that offers some courses in entomology.

Arachnologists get to study these cool things… Photo by Sean McCann.

Off to college!

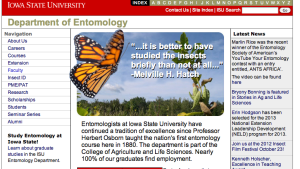

There are virtually no Arachnology programs at colleges or Universities, and instead college student should look to the sister discipline of Entomology. Many (most?) Universities offer some introductory entomology courses, and in these courses it may be possible to get some exposure to Arachnology. The instructors of these course can probably help point to other resources or local people with additional expertise or interest in arachnids.

When seeking an undergrad program, I do advise aspiring arachnologists to take a strong Biology or Zoology Major: this will give a great grounding and foundation and be perfect for a springboard to graduate school. It’s certainly worth considering selecting a University that has an entomology program, or at least a Department or solid offerings of insect-themed courses, and has some arthropod-themed research happening.

If time and money permits, there are some “spider courses” out there and perhaps it’s worth taking one of those (although I have never taken one, I have heard they can be quite worthwhile). At the very least, do LOTS of reading, including books like The Biology of Spiders and field guides like Rich Bradley’s (for North America), and stay active on social media.

Becoming an arachnologist is about finding good mentors: these people may or may not be arachnologists, but their encouragement and support is so important and can change lives. This was certainly the case for me, and an entomologist at University of Guelph helped facilitate my interests in Arachnids and gave me a desk to work at, and offered plenty of encouragement. My independent undergraduate research project about spiders set me on a path to becoming an arachnologist.

It’s a bit of a shame, and a bit of a mystery that Arachnology just doesn’t show up on the radar for very much of K-12 nor does it show up in undergraduate programs: becoming an arachnologist with a deeper level of training really happens at graduate school, so for those who are really passionate about arachnids may need to take a long view and plan on moving on to a Master’s degree. This certainly doesn’t mean you can’t be an arachnologist in other ways! (Some great Arachnologists I know don’t have advanced degrees). However, the more advanced training can help formalize and structure the learning process.

Meet Catherine! She’s an Arachnologist, and is searching for spiders… Photo by Sean McCann

How do you know you are an Arachnologist?

This is a great question, and a difficult one to answer! There certainly isn’t a certificate or plaque that you get once you become trained as an Arachnologist. As you accumulate knowledge you will also realize that there is so much we don’t know about Arachnids. New species are described all the time, and we continually hear amazing stories about their natural history. Expertise is all relative, and once some expertise is acquired, the limits of our knowledge become exposed.

You don’t need to publish in scientific journals or do experiments on spiders to become an Arachnologist. You do have to learn some biology and arachnid natural history, and do your best to share what your know with others. Bottom line: once you have acquired enough knowledge about Arachnids, and people start looking to you for advice and answers to their own questions about our eight-legged friends, you can probably call yourself an Arachnologist.

So, to sum it up: to become an Arachnologist you need to read, watch, connect, share & study.

But..

Are there jobs for Arachnologists? That’s a topic for another post…

Robb Bennett: a most exceptionally wonderful person (and Arachnologist). Photo by Sean McCann.