Natural history can be defined as the search for, and description of, patterns in nature. I see natural history research as a more formal and structured approach to studying and recording the natural world. I also see this kind of research as a branch science that is often driven by pure curiosity. Many well-known and popular scientists are naturalists (ever hear of David Attenborough or E.O. Wilson?), and we can see that curiosity is one of the underpinnings of their work and personalities. Natural history research is, without doubt, very important, but in world of academic research, it sure doesn’t headline as pulling in multi-million dollar grants, nor does “natural history” appear in the titles of high profile research papers.

Is there a place for curiosity-driven natural-history research in today’s science? If so, how do we study it in the current climate of research?

Arctic wildflowers. Worthy of research… just because?

This is big question, and one that we grapple with occasionally during my lab meetings. Most recently this came up because I challenged one of my students when they wrote about how important their research was because “…it hadn’t been done before“. In the margin of their work, I wrote “…so what? You need to explain how your work advances the discipline, and the explicit reasons how your research is important independent of whether or not it has been done before“.

Am I wrong? Is it acceptable to justify our research endeavours because they haven’t been done before?

The context matters, of course: some disciplines are very applied, and the funding model may be such that all or most research is directed, project-oriented. The research may have specific deliverables that have importance because of, perhaps, broader policies, stakeholder interests, or needs of industry. In other fields, this is less clear, and when working in the area of biodiversity science, such as I do, we constantly stumble across things that are new because they haven’t been studied before. And a lot of these ‘discoveries’ result from asking some rather basic questions about the natural history or distribution of a species. These are often things that were not part of the original research objectives for a project. Much of natural history research is about discovering things that have never been known before and this may be part of the reason why natural history research isn’t particularly high-profile.

Here are just a few examples of interesting natural history observations from our work in the Arctic:

This is the first time we observed the spider species Pachygnatha clerki on the Arctic islands!

Wow, we now know that an unknown parasitoid species frequently parasitizes the egg sacs of a northern wolf spider species!

Females of this little pseudoscorpion species produce far more offspring than what had been previously documented!

Now, if I wanted to follow-up on any of these observations, I think it’s fair to state that the research would be curiosity-driven, and not necessarily grounded in a theoretical or conceptual framework. It’s the kind of research that can be rather difficult to get funded. It’s also the kind of research that is fulfilling, and a heck of a lot fun.

I’m likin’ these lichens. And surely data about them is required…

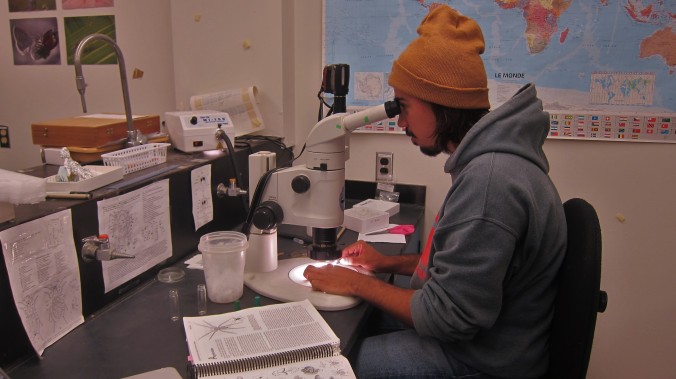

How then do you study such fascinating aspects of natural history? How do you get out to the field to just watch stuff; record observations just for the sake of it; spend time tabulating life history parameters of a species just because it’s interesting?

Perhaps you have the luxury of doing natural history research as your full-time job: You may be able to sit back and have people send you specimens from around the world, and maybe go out on an extended collecting trip yourself. You may be lucky enough (and wealthy enough?) to devote serious amounts of time to “think”, measure and record data about species. Perhaps you can even take a long walk each day to mull over your observations. Maybe you will gather enough observations to eventually pull together some generalities and theories, and perhaps you will get around to writing a book or manuscript about this….

Reality check: Most of us don’t have that luxury. Instead, we chase grants, supervise students, do projects that fit in with our unit’s research area, and publish-or-perish in the current model of academic research. Despite how we might long for the “good old days” of academia, they are gone (at least in my discipline). It’s rare that a University Professor or research scientist is hired to do stuff just to satisfy her or his own curiosity.

That main sound depressing to some, and hopeless, but it’s not meant to be. I do believe there are still ways to do exciting and interesting natural history research, and we can call it research by stealth.

In my field of study, establishing a research programs means getting grant money, and these are often aligned with priorities that matter to government, to policy, or to a particular environmental threat such as climate change or invasive species. It’s important to get these grants, and work with students and collaborators to try to solve some of the large and complex problems of the world. I am not advocating avoiding this. Instead, as we move along with these big projects, there are also countless opportunities to do a little natural history research, by stealth. Our first priority may not be the collection of natural history data, but nothing stops us from finding creative ways to make careful and meaningful natural history observations.

When taking a lunch break on the tundra, take a little longer to watch the Bombus flying by, or write down some observations about the bird fauna in your local study site, even if you aren’t an ornithologist. Keep a journal or sketch a few observations while you are sitting in the back of the field truck on that long drive up to the black spruce bogs. Each year, buy a field guide for a different taxon, and learn new stuff alongside your focused project. This ‘spirit’ of natural history observation is one that I promote to my own students, and I encourage them to follow up on some of these as a side-project to their main thesis research. Often, these end up being published, and end up in a thesis, and they certainly end up informing us more about our study species or study area.

Lunch break on the tundra: an opportunity for natural history observations

Despite writing all of this, I still think my comment in my student’s writing will remain: we have to look at the importance of our research in the context of the bigger picture - it’s not enough to say something is important because it hasn’t been done before, and I’m not sure a PhD thesis can (or should) be entirely based on natural history observation. I would not be doing my job as a supervisor if I promoted curiosity-driven natural history research as the top priority for my student’s projects. To be candid: they won’t get jobs or publish papers in the higher profile journals (i.e., those ones that matter to search committees), and they won’t be well equipped when they leave my lab and head to another institution.

…But I will promote natural history research by stealth.

I think there is loads of room for curiosity-driven natural history research in today’s science. We may need to be creative in how we approach this, but, in the end, it will be worth it. We satisfy our curiosity, and learn a little more about the world along the way. We will also gain perspective and experience, and my students will be well equipped for a future in which natural history research is valued more highly then it is now.