Here’s a hypothetical scenario:

Q: “Hey I see you published a paper that shows the wolf spider Trochosa ruricola occurs up in the Ottawa Valley - I didn’t realize it had reached that far. It’s an invasive species, so tracking its distribution is quite important”

A: “Yeah, we too were surprised it was up that far: to our knowledge, only Trochosa terricola was in that part of Ontario”

Q: “It is tricky to tell apart those two species! What museum did you deposit specimens in? I’d like to take a look at them to verify the identification.”

A: “Um, we didn’t get around to depositing specimens in the museum. There might still be some in the lab. I’ll have to get back to you...”

Not cool. And also much too common.

Bottom line: when specimen-based research is done with arthropods, whether it is a biodiversity inventory, a community ecology study, or a taxonomic revision, the researchers must deposit voucher specimens in a research museum or institutional collection. This is only way to truly verify that the work is accurate, that people are calling things by the same name, and it puts a stamp in time for the research. Without deposition of these voucher specimens (somewhere that is publicly accessible and curated, and along with data about time, place and collector) the research cannot be verified, and this goes against the principle of repeatability in science.

Beetles in drawers: a great example of specimens in a curated museum, and shows how such specimens can be used for all kind of research!

This is a no-brainer, right? It’s time to test whether or not scientists actually bother to deposit voucher specimens…. As part of a graduate-level* class in Entomology last winter, we surveyed the literature to find out the frequency of voucher deposition with arthropod-based research. We looked at papers to see what percentage actually report on vouchers, assessed whether the frequency of voucher deposition varied by research type, study organisms, institution (of researcher), and whether voucher deposition has changed over time.

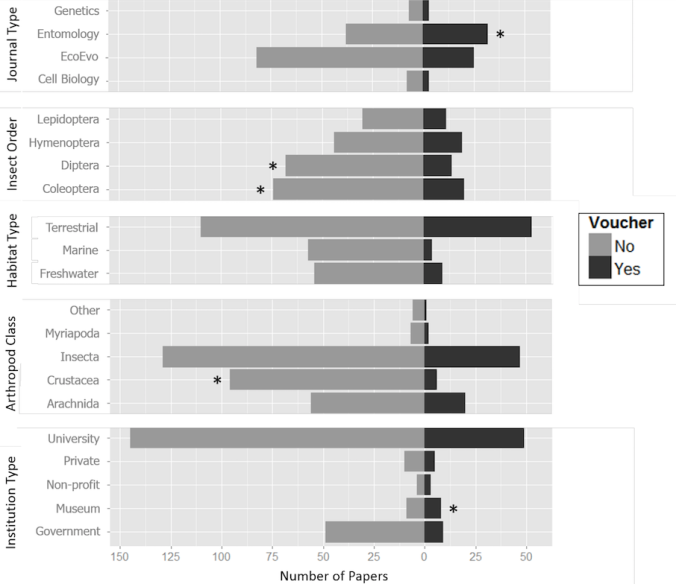

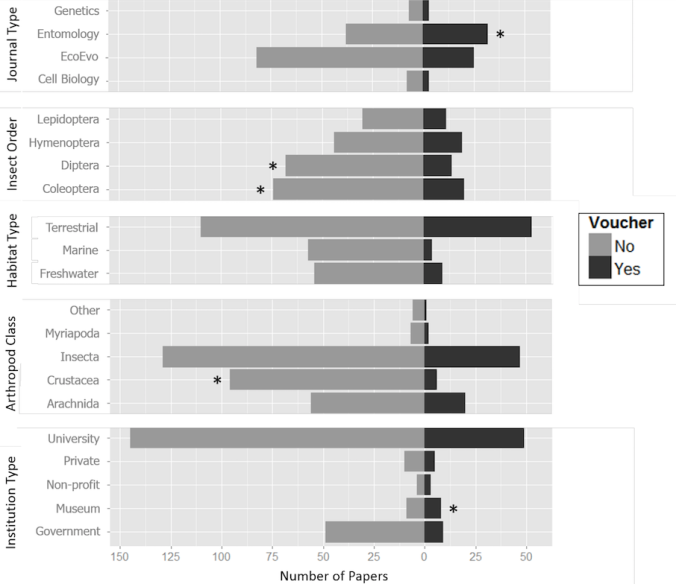

We published the results a few weeks ago, in the Open Access journal PeerJ, and our work has revealed a crisis in arthropod-based research. Overall, rates of voucher specimen deposition were very low, as only 25% of papers report on the deposition of voucher specimens. This is horrible, and essentially means that the specimens from the majority of papers published cannot be traced to a collection, and cannot be verified.

Some disciplines were worse than others, as crustacean researchers deposited vouchers only 6% of the time, as compared to the relatively higher rate of voucher deposition by entomologists, at 46%. Here is a summary of the main findings:

The main findings of our research: the asterisk illustrates a significant difference relative to a global mean. Figure from our paper, published here.

Is there any good news? Perhaps so… when looking at rate of voucher deposition over time, more papers are reporting about vouchers in 2014 (35%) compared to 1989 (below 5%).

At the end of our paper we provide some conclusions and recommendations, and these are repeated here:

- PIs must be responsible and proactive on the process of voucher specimen deposition, from the start of any project.

- Graduate students need to be mentored appropriately about the importance of voucher specimen deposition.

- It needs to be recognized that voucher specimens are important for all branches of arthropod research - there is no reason that entomologists should do better than, say, crustacean biologists.

- Close collaboration between Universities/Research Centres and Museums is required, so that there is an agreed up, and easy process for all researchers to deposit vouchers.

- Everyone involved with arthropod-based research needs to work together to push for long-term, sustainable funding for institutional collections/museums so that proper curation of vouchers can be done.

- Publishers and editorial boards need to have clear policies about voucher specimens, so that any papers published are required to report on vouchers.

I recognize that the title of this post is provocative. Is it *really* a crisis?

I think it is: I think that even the best rate of voucher deposition that we report on is too low. We must aim to be closer to 100%. It’s important as we work to describe the world’s biodiversity, understand what is happening to our species in the face of climate change, or track the distribution of invasive species. It’s important that our hard work is more than a publication: our hard work is often a specimen, and that specimen needs to be accessible for future generations.

Voucher for critters than need to be stored in liquids looks something like this.

Reference:

Turney S, Cameron ER, Cloutier CA, Buddle CM. (2015) Non-repeatable science: assessing the frequency of voucher specimen deposition reveals that most arthropod research cannot be verified. PeerJ 3:e1168 https://dx.doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1168

* A most sincere thanks to my graduate students Shaun, Elyssa and Chris - these students did the lion’s share of this project, and took on this graduate class with great enthusiasm, maturity and motivation. You all inspire me!