What will the University of 2050 look like?

This was the fundamental question that guided a three day workshop /conference /event that I attended last weekend (you may have seen some activity on Twitter about this!). It’s a very difficult question, but an important one! Conference attendees prototyped a future university but did this in a very structured way, starting with a discussion (on the first day) about the “core values” that need to remain in University 35 years from now. There was general convergence around these values: critical thinking and unfettered curiosity, access & freedom of expression, diversity, community, and the importance of person-to-person interaction.

The second day was devoted to discussions about “game changers” - broader factors that might challenge the core values of Universities. These game changers included external factors such as shifting geopolitics or environmental catastrophes, to technological advancement such as artificial intelligence, “holodecks”, cognitive enhancement or ever-increasing life expectancy (and its implications), or some kind of Black Swan event.

Day three was about designing a future University given the core values and given the influence of game changers.

Here’s my group’s vision* for an institute of Higher Education in 2050: an institute we called “Horizon University”.

—-

Horizon University is still a campus, but is part of a globally connected network of Universities. Campus remains as a physical space for intellectual discussion, social engagement, clubs, activities, and a safe space for its students. The students themselves are from around the world, and many are returning to University after holding down a first (or second) career for many years. Although many students may attend HU classes virtually, there will still be students who will be present, physically, in classes. There are no longer large lecture halls, and instead HU is comprised of suites of collaborative learning spaces. Enrolment in a class may be large but the number of participants in each room remains small: the instructor’s avatar can move among the rooms. Students are paired with peers in most activities, and collaborative learning is the norm.

Our group’s visual representation of Horizon University, warts and all.

Failure is also the norm: the process of learning takes precedence. The instructor is less a “professor” and more of a facilitator, largely because the sum of all information is at everyone’s fingertips (or implanted in our neuro-cortex). The classes are mostly “topic” or “project” based, because Universities are nimble, agile, and a place in which research and teaching are focused on society’s needs and struggles, although there remains places and spaces to discover for the sake of discovery. Professors still exist as subject experts, but are never working in isolation. Learning is truly interdisciplinary.

Classes run 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and individuals from outside of HU may (virtually) drop into classes that are of interest to them. Many of the administrative functions of HU itself are largely run with the help of AI (artificial intelligence). In fact, AI acts as a type of “virtual assistant” for students: helping students schedule and get to class, checking in on their health and wellbeing, and doing the (objective) course assessments (i.e., to divorce this from the act of instruction), and doing the credentialing (assuming some kind of “degree” is still granted). The AI assistant can pick up on cues related to student wellbeing, and help get a student in to see a real person whether it is for counselling, advice, or to meet the facilitator for a course they are following.

—-

Our group then assessed what important actions would be required to see Horizon University come to fruition, and we felt there needed to be, in this order, (1) equality (ie, at a global scale), (2) teams of people to develop AI, (3) interdisciplinarity (within and among institutions) (4) rethinking the concept of “9 to 5” to the concept of “24/7” education, and (5) complete redesign of all learning spaces.

We then thought about the feasibility of those five actions, into the future, and came up with the following order: (1) learning spaces, (2) AI development, (3) 24/7 scheduling, (4) interdisciplinarity, and (5) Equality

Clearly feasibility doesn’t align with the importance of the actions, which is itself interesting, and challenging!

Caveats: I don’t believe everything we came up with, nor should you. Our group didn’t agree all of the time, and there are certainly some rather large flaws in some of the ideas, the logic, and the entire model may not be economically feasible.

But it doesn’t matter: it’s about the discussion. It’s about reflecting on the things we value in a university and the challenges we face. It’s about charting a path forward in an increasingly technological age and an age where research and knowledge is moving in new directions and where we are questioning fundamental concepts around teaching and leaning. Prototyping a University in 2050 is about starting a conversation and being part of an incredibly exciting time.

On a more personal level, the most valuable part of the experience was learning from people from different places, different career stages, and from different perspectives. The conference included writers, artists, computer programmers, undergrad and grad students from a suite of disciplines (e.g., humanities, social sciences, and STEM), professors, university administrators and more. It forced me to open my mind, listen, and reflect on my own biases. There is so much value in diversity, and tackling questions about the future of University means bringing in as many stakeholders as possible.

I leave you with a few questions:

What do you envision as the future of your own institution?

What are your ideas about how to maintain core values of a university in the face of game-changers?

How can technology facilitate higher education?

Have you had this discussion at your own institutions? If so, what have you learned?

Please join the discussion. And you can follow the Event Horizon Blog here.

Postscript: the day after the conference I did some field work in an amazing forest near Montebello Quebec (see photo, below). What a contrast after three days of intense discussions, full of technology, data and information! I breathed in fresh air, watched some butterflies for a while, heard the birds singing and there was no cell reception. It was wonderful, refreshing and uplifting. This had me reflecting a bit more about a University of the future, and how that University should perhaps be much more closely integrated with our natural systems. That would be a good goal.

The forest.

——-

* I hope I have adequately described the key aspects of our group’s vision - it was more detailed then what I have presented, and I wholeheartedly admit that my writing may not reflect everyone’s opinion of our prototype University. (Sorry if this is the case!)

© C.M. Buddle (2015)

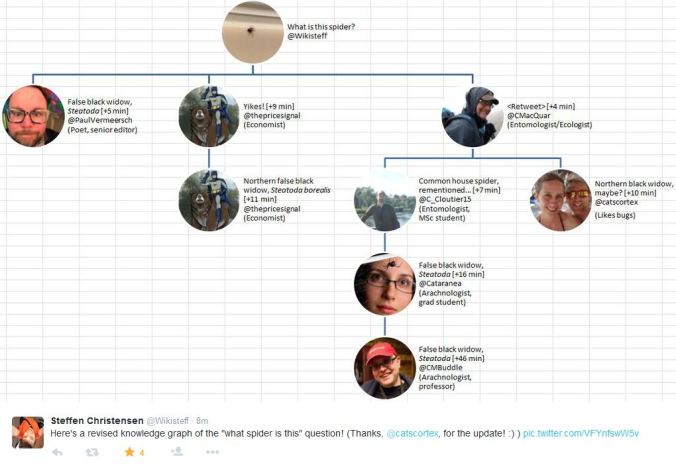

![Active Learning: Watisoni Lalavanua (l) and Josh Drew (r) [tweeting!] at the Suva Fish Market, identifying species and talking about the best way to manage fisheries based in their life histories.](../../2015/05/fish-market_w-676-h-509.jpg)