Dear Instructors,

Here’s your challenge: Include active learning activities in every lecture.

Just do it.

Active learning is a philosophy and approach in which teaching moves beyond the ‘podium-style’ lecture and directly includes students in the learning process. There is certainly a big movement out there to include active learning in the classroom, there is evidence that it works, and active learning strategies have been around for a long time. Active learning can make learning experience more interactive, inclusive, and help embrace different learning styles. Active learning places the student in a more central role in a classroom, and allows students to engage with the course and course content in a different way.

So, why doesn’t everyone embrace active learning?

Without a doubt, it can take a bit of extra work. This post by Meghan Duffy provides an excellent case study, and illustrates the benefits and drawbacks of embracing a ‘flipped classroom’ in a large biology class, and part of that involves heaps of active learning strategies.

Active learning also involves some risk-taking, and perhaps risks that pre-tenure instructors should avoid. The strategies can remove some of the control of the instructor, and this can be uncomfortable for some teachers. For any active learning strategies to work, the instructor, and students, need to be on board, and each strategy brings some challenges, takes time to prepare, and certainly takes time in the classroom.

This term, in my 70+ student ecology class, I decided to take the active learning challenge, and, every lecture, include active learning*. I want to share a few of the things I have done so far, and hopefully show that some ideas are easy and doable, for pretty much any teaching context (note: I do use this book to help generate ideas)

1) The teacher becomes the student: for the last five minutes of class, I pretended to be a student, and asked the students to become the teacher. I then asked them some questions about the course content, drawing upon material from the last couple of lectures. Because I have taught the course for many years, I had a good sense of where some ‘problem areas’ may be, and thus formulated questions that got to the more difficult material. Students then were able to respond to my questions, and share their own expertise with the whole class.

2) Clear and muddy: at the end of one lecture, I asked the students to write down one part of the content they really understood well (the clear), and one area that might be “the muddiest point” (i.e., what they are struggling with). Students handed in the pieces of paper, and I went through and sorted them, and then spent part of the next lecture re-explaining common muddy areas. This was a terrific way to get anonymous feedback, helped reinforce areas that I perceived to be going well, and allowed me to target problem areas in the course.

Here’s a “muddy” - this student’s comment reflects a common concern around how I teach some of the content.

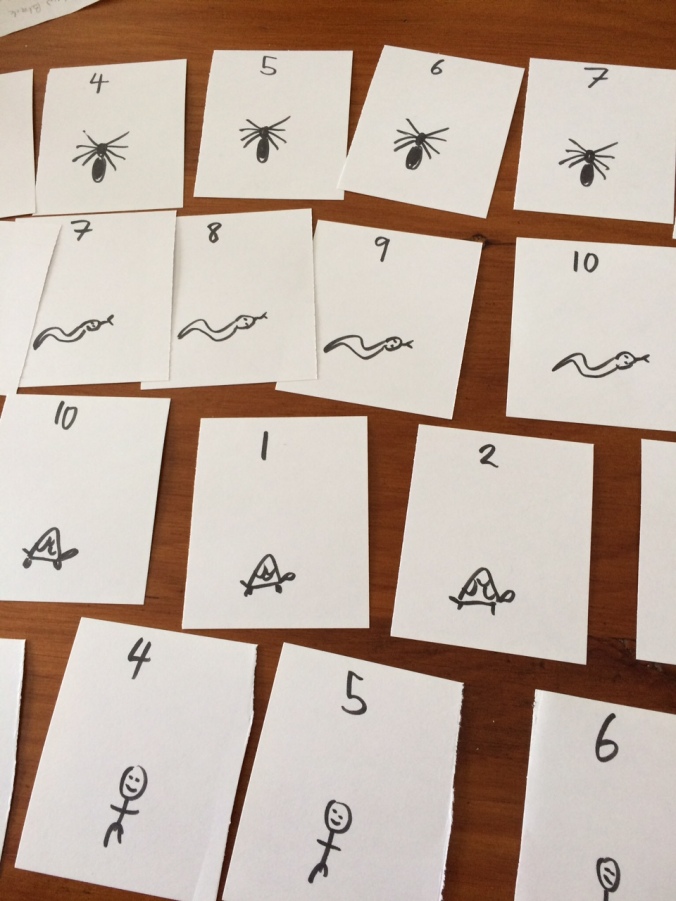

3) Gather in groups: many active learning strategies work best when students are in groups. To quickly set up groups during class, each student holds a ‘card’ with different symbols, letters, numbers, and drawings, and when I call out one of these, the students form groups. I made the cards so students get sorted into groups of different sizes, depending on the activity.

An easy and effective active learning strategy with groups is to have student discuss among themselves a particular problem or question. After a few minutes, a spokesperson can report back their findings to the whole class. I’ve also had some students come to the front and present the result to the class. This does depend on having ‘enthusiastic’ volunteers, but I have not found this a barrier.

4) IF-AT cards: this term, I am trying to use Instant-feedback assessment-techniques for multiple choice questions. These cards allow students to scratch off answers on a card, and they immediately know if they are right and wrong, and can scratch a second or third time to receive partial points. I have used these in the classroom, for group work, and then students can work on problems (presented by me on the blackboard or screen), debate and discuss the answers, and then scratch off to reveal the correct answer. This activity therefore includes group work, problem solving, discussion and debate, and instant feedback. It does take a little bit of time (20 minutes or so, for a few questions), but is an effective active learning strategy that combines learning with an instant-feedback style of assessment.

5) Pair and share: this is also a simple and effective way to get discussions happening in lecture. I pose a question or idea, and simply have students turn to their neighbour to discuss the answer. I then ask some of the pairs to share their answers or ideas, and I also divide the lecture hall into different sections and ask pairs from each section to report back. This allows full use of the space in the classroom and students at the backs, fronts, or sides are able to feel included.

All of the abovementioned strategies don’t actually take that long and do not require a major overhaul to the course or course content. I believe they are relatively risk-free and easy, and suitable for any instructor, pre-tenure or not. I see these kinds of active learning strategies more as ‘value added’ activities, and as small steps that can increase student engagement in the classroom.

I also teach with chalk, as I find that’s a great way to make the classroom more active, for everyone.

——-

* Full disclosure: so far I have succeeded in all but one lecture, and I’m eleven lectures in. I’ll post an update at the end of term, to let you know if I’m successful all term!