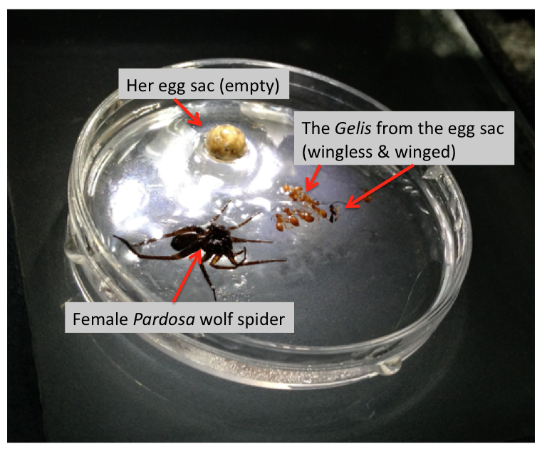

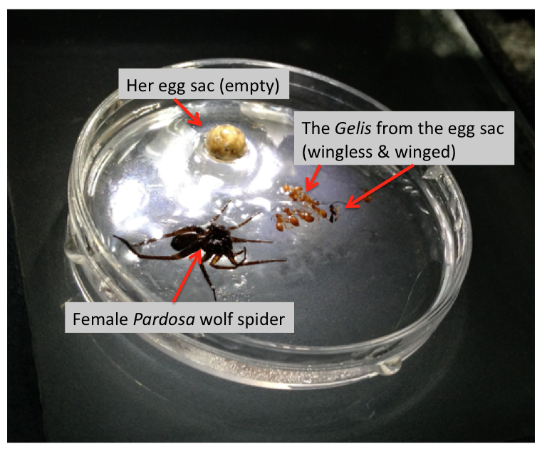

This week we are in a deep freeze in the Montreal area, so it seems somewhat fitting to discuss Arctic spiders. I’ve discussed the life-history of Arctic wolf spiders (Lycosidae) before, specifically in the context of high densities of wolf spiders on the tundra. Much of this work was done with my former PhD student Joseph Bowden. The latest paper from his work was published last autumn, and was titled ‘Egg sac parasitism of Arctic wolf spiders (Araneae: Lycosidae) from northwestern North America‘. In this work we document the rates of egg sac parasitism by Ichneumonidae wasps in the genus Gelis. These wasps are fascinating, and we have found them to be very common on the tundra. There are often multiple wasps in a single egg sac, and as is typical with Gelis, they leave nothing behind: all eggs within an egg sac are consumed. After fully developed, the adult wasps pop out of the egg sac; the Gelis adults we encountered had both winged forms and wingless females, the latter superficially resembling ants.

The rates of parasitism of Pardosa egg sacs (by Gelis) were, at some sites, extremely high. In some cases over 50% of the wolf spider egg sacs were parasitized. Stated another way, half of all the females encountered with egg sacs had zero fecundity because the female was carrying around wasps within the egg sac instead of spider eggs.

It’s quite interesting to think about these wingless Gelis females: after emerging from egg sacs, they end up wandering around the tundra in search of hosts. Spiders with egg sacs must be encountered frequently enough for the wasps to grab on to a passing wolf spider in order to parasitize the egg sac. Recall, densities of wolf spiders can be very high in the Arctic (4,000 per hectare, at least). Hmmm…. this is all starting to fit… high densities of wolf spiders support high rates of egg parasitism and these wasps can ‘afford’ to be wingless since their hosts are frequently encountered: an interesting feedback loop! We can also speculate about large-scale gradients in diversity - many Ichneudmonidae show high diversity in northern regions. Within Gelis, it’s a good bet that they will find many suitable spider hosts in these environments.

Looking down the microscope - all those Gelis!

So, how extreme are these rates of egg parasitism? Looking at some of the literature, there are certainly a number of papers about wasps that parasitize spider egg sacs. Cobb & Cobb (2004) studied two Pardosa species in Idaho, and recorded a egg parasitism rate of about 15% (by Gelis wasps and wasps in the genus Baeus [Sceleonidae]). Van Baarlen et al (1994) studied egg parasitism in European Linyphiidae spiders and their maximum rates of parasitism were about 30%. Finch (2005) did a detailed study of four spiders species (non-Lycosidae) and rates of egg parasitism varied between 5% up to as high as 60% in an Agroeca species.

Our documented parasitism rates for Arctic wolf spiders are certainly quite high (for Lycosidae), but not out of the range of other published studies for non-Lycosidae. I do wonder whether we will continue to find high egg parasitism rates if more species were examined in detail - certainly a fertile area of study. Related to this, what are the population-level consequences of this interaction? What is the relationship between spider densities and parasitism rates? Although Joe and I did try to speculate on this, our data are preliminary - again, a key area for future research.

In the Arctic context, we will continue to uncover fascinating food-web dynamics. Our research group has already been thinking seriously about this - Crystal Ernst has written a nice post about the idea of an ‘inverse trophic web’ (i.e., predator-dominated) in the Arctic, and a fair amount of my future research will pursue this avenue of research.

Pique your interest…? Why not think about graduate school in my lab, and study Arctic arthropod biodiversity?

References:

Bowden, J., & Buddle, C. (2012). Egg sac parasitism of Arctic wolf spiders (Araneae: Lycosidae) from northwestern North America Journal of Arachnology, 40 (3), 348-350 DOI: 10.1636/P11-50.1

Cobb, LM & Cobb VA (2004). Occurrence of parasitoid wasps, Baeus sp and Gelis sp., in the egg sacs of the wolf spiders Pardosa moesta and Pardosa sternalis (Araneae: Lycosidae) in southeastern Idaho. Canadian Field Naturalist 118(1); 122-123.

Baarlen, P., Sunderland, K., & Topping, C. (1994). Eggsac parasitism of money spiders (Araneae, Linyphiidae) in cereals, with a simple method for estimating percentage parasitism of spp. eggsacs by Hymenoptera Journal of Applied Entomology, 118 (1-5), 217-223 DOI: 10.1111/j.1439-0418.1994.tb00797.x

Finch, O. (2005). The parasitoid complex and parasitoid-induced mortality of spiders (Araneae) in a Central European woodland Journal of Natural History, 39 (25), 2339-2354 DOI: 10.1080/00222930500101720